By GLENN KESSLERS

“Are Republicans in Congress really willing to let these cuts fall on our kids’ schools and mental health care just to protect tax loopholes for corporate jet owners?”

— President Obama, weekly radio address, Feb. 23, 2013

“Perhaps the most egregious part, as I was saying, is that you can take a particular tax loophole, the tax break that you get if you buy a corporate jet — $3 billion — that taxpayers are having to cover in costs that corporate jet owners would otherwise pay to the federal government. You can eliminate that tax loophole, and save yourself the $3 billion, so you wouldn’t have to go after the 600,000 women and children who will lose their critical nutrition assistance program. Or you can use that money to make sure that 125,000 families under the Ryan budget who are slated to lose their housing, won’t lose it.”

— Rep. Xavier Becerra (D-Calif.), news conference, March 18, 2013

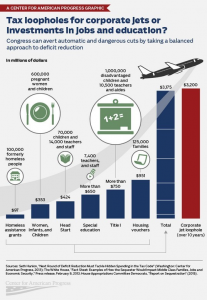

The corporate jet “loophole” has wonderful symbolic value, as illustrated by the chart above prepared by the Center for American Progress. And, as the quotes above illustrate, Democrats love to cite it as an example of heartless choices made by Republicans. The @BarackObama twitter account even tweeted out an image of the CAP chart.

We obviously take no position on whether the specific tax treatment of corporate jets is good or bad. But how fair a comparison is this?

The Facts

As best we can determine, in 2004 then-Rep. Rahm Emanuel (now mayor of Chicago) first drew attention to this provision in the tax code when he testified at a hearing designed to highlight ways to improve the tax system. Now, nearly 10 years later, it remains a potent symbol.

But as a Reuters article this week pointed out, this is not so much a loophole as a different way of depreciating the assets. Essentially, corporate jets and other general aviation aircraft depreciate over five years, compared to seven years for commercial jets. Eliminating the tax disparity would effectively boost the cost of buying a plane because only about 14 percent of the purchase price could be deducted each year, compared to 20 percent currently. As Reuters said.

The U.S. tax code treats private aircraft as it does bulldozers, computers and other business equipment: Companies that buy them are allowed to deduct the cost from their tax bill over five years. The deduction applies only to planes used for business purposes.

The depreciation schedule has been in place for decades. It is supposed to reflect how long a product will be useful to a business. But private planes and factory machinery can be used for decades, while computers and mobile phones can become obsolete before the five-year depreciation period expires.

Sounds kind of odd, doesn’t it? In 2005, former Treasury official Thomas S. Neubig testified that “the present law class life tax depreciation classification system is primarily based on a Treasury study of corporate income tax returns from 1959” and that “only modest changes to the underlying depreciation class life classification system have been made to the class life classification during the past 45 years.”

This raises a broader question: Does either the five-year or seven-year schedule reflect the actual economic life of an airplane? Not really, given that planes are built to last for many years, if not decades. Perhaps that should really be the subject of debate.

Finally, is a commercial jet the same thing as a smaller plane? Some opponents have argued that Obama would also be targeting crop-dusters and other such aircraft. We looked up the Treasury Department’s description of Obama’s tax proposal (see page 132) and it appears to carve out an exception for any aircraft that does not carry passengers–while at the same is not quite limited to just “corporate jets”:

The proposal would define “general aviation passenger aircraft” to mean any airplane (including airframes and engines) not used in commercial or contract carrying of passengers or freight, but which primarily engages in the carrying of passengers (other than an airplane used primarily in emergency or emergency relief operations).

Any airplane not used in commercial or contract carrying of passengers or freight, but which is primarily engaged in non-passenger activities (e.g., crop dusting, firefighting, aerial surveying, etc.) and any helicopter would continue to be depreciated using a recovery period of five years.

Meanwhile, changing just this minor quirk in the tax law would raise just $300 million a year, or perhaps $3 billion over 10 years. (As we have noted before, it’s hard to predict what eliminating a so-called tax expenditure will really yield.)

So this is really chicken feed compared to the really big ticket items such as the mortgage interest deduction, which reduce tax revenues by hundreds of billions of dollars over just five years.

The CAP chart was specifically designed to suggest a replacement for the automatic spending cuts known as the sequester. Note that it takes the 10-year figure for the corporate jet “loophole” and then compares that figure with what are essentially seven months worth of spending.

We didn’t think that was quite kosher.

Melissa Boteach, who produced the chart, defended the math by saying that “in all likelihood, any deal to replace this year’s sequester will be paid for over 10 years.” She noted that an earlier two-month delay in the sequester, reached as part of the fiscal cliff negotiations, was paid in part with 10 years of savings.

“There’s no reason to let these painful cuts devastate the lives of people and communities across the country when we know there’s low-hanging fruit like the corporate jet loophole that can be used to turn off the cuts while we work toward a long-term deal,” Boteach said.

Republicans don’t necessarily oppose changes to this provision, but want it as part of a comprehensive package. House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) “believes we should reform the entire tax code. We should clear out the unjustified carve-outs, so we can lower the hurdles to job creation,” said spokesman Conor Sweeney.

The Pinocchio Test

Symbolism can be potent, as the White House recently learned after the blowback from its decision to save funds by canceling White House tours.

But this assertion skates right on the line up to demagogy, posing the choice as between starving children and corporate fat cats.

The numbers appear okay — and Boteach’s explanation for using 10-year numbers has a ring of truth, given that Congress often pays for one-year fixes with 10-year payouts.

But this is basically a relatively minor tax disparity, rather than a “loophole.” Given that the depreciation system in general is woefully out of date, it’s misleading to focus just on this single quirk, no matter how alluring the symbolism.